In the hands of a lesser talent, Savages might have just been a run of the mill crime flick. But with his mastery of the medium, movie maestro Oliver Stone’s highly charged, absorbing adaptation of Don Winslow’s novel becomes a Joseph Conrad meets Film Noir rumination on human nature, and the lengths men — and women — will go to in order to fight for what they value most.

And the gloves — and heads — are off on this long strange cinematic drug fuelled trip, as SoCal stoners do battle with a Mexican cartel. Kathryn Bigelow’s 2008 The Hurt Locker finally explained why the U.S. invaded an Iraq minus WMDs when [PLOT SPOILER ALERT!] the Arab boy peddling pirated DVDs was blown up: Bush and Rumsfeld were trying to stop theft of intellectual property. Now, director/co-screenwriter Stone has finally explained why U.S. troops are still in Afghanistan: To develop and export the world’s finest quality cannabis.

[PLOT SPOILER ALERT!] Ex-Navy SEAL Chon (Taylor Kitsch) encounters this natural born killer weed during his tour of duty in ’Stan. In between deployments, Chon joins forces with Ben (Aaron Johnson), who majored in business and botany at (where else?) Berkeley. Together they grow and sell this boutique pakalolo, getting rich in the process. The entrepreneurial duo becomes a cross between pot’s Ben and Jerry and Cheech and Chong, living the high life at the so-called “paradise” of Laguna Beach with their mutual gal pal Ophelia. (Yes, Gossip Girl Blake Lively’s monicker is indeed inspired by what her character calls Hamlet’s “basket case who committed suicide.”)

Alas, the success of Ben and Chon Inc. and their stellar strain of splendor in the grass has not gone unnoticed south of the border. Following the laws of capitalism — with its internal “logic” of growth, expansion, mergers, acquisitions and monopolization, and that lack of empathy which is the capitalist’s hallmark — a Tijuana-based drug cartel tries to make the Laguna lads an offer they can’t refuse, demanding that they supply. But Ben and especially Chon, the ex-SEAL — who says they “want us to eat… shit and call it caviar” — smell a sewer rat, and all hell breaks loose.

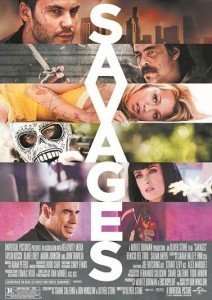

In this metaphor of contemporary capitalism, the individual entrepreneurs wage war with the corporate monopoly. The ensuing mayhem gives whole new meaning to the phrase “Wasted away again in Margaritaville.” Spitfire Salma Hayek plays the cartel chief Elena, a lonely femme fatale with mommy issues, while Benicio Del Toro is her ruthless, scheming henchman Lado. Those who get in the way of these vicious narco-traffickers have a habit of losing their heads — literally. The brutal cartel also has a unique form of severance pay for employees whose services are no longer required — a bullet in the skull. Throw into this combustible mix John Travolta as Dennis, a DEA agent who picks sides with the same fidelity Mitt Romney hews to various sides of the same issue.

Ultimately, this is the essence of Savages: Loyalty. What is a more powerful unifier? The lust for money? Or love — between mother and daughter, and especially between Ben, Chon and Ophelia? Is their threesome mightier than the sword? Is their ménage-a-trois — an ersatz family created by these waifs in lieu of the family they never had — a greater unifying force than greed?

Like Conrad’s Congo-set Heart of Darkness, Savages reveals that beneath one’s civilized persona beats the heart of a barbarian. Given the circumstances, what measures might a desperate man — or woman — take to protect loved ones, money, etc.? In interviews Stone has likened Lively to Grace Kelly, and this is particularly apropos regarding what may well be the best film Kelly was in, the 1952 Western High Noon, wherein her Quaker newlywed set aside her pacifism to stand by her man — even if it involved gunplay. This Grace Kelly/High Noon analogy not only may hold true for Lively’s Opehlia, but for Ben, the high on life humanitarian who spends part of his ill gotten gains on a foundation helping developing nations. When the chips are down, this idealistic Hamlet overcomes procrastination and reluctance to rescue his Ophelia — by any means necessary.

The ménage-a-trois between Ben, Chon and O (as Ophelia is generally called in Savages) is intriguing. Stone calls it “Jules and Jim meets Scarface,” and it’s refreshing to see sexual relationships depicted onscreen that are outside of the usual monogamous box human sexuality is confined in. When it comes to romance, one size definitely does not fit all. However, aside from the derrieres of the two leading men and a topless Mexican character (presumably a prostitute Lado has hired), the lead white actress is never seen nude. What a double standard: Brown nipples can be bared, but not pink ones. Stone told me the film’s limited nudity was due to MPAA restrictions (paging Kirby Dick!) and thespian concerns, but Savages has an “R” rating — mainly because of its drug use and no holds barred violence — anyway, so how would nude shots of, say, Lively, Hayek or the actress playing her daughter Magdalena (Sandra Echeverria) have affected the movie’s rating? And if a star does not want to bare all, there’s a new invention: Body doubles. By eschewing most nudity the picture loses some of its power and edginess — especially a film titled Savages. How American: A U.S. filmmaker can show beheadings but not performers giving head. And that’s the naked truth.

Be that as it may, Stone skillfully directs his ensemble cast, which includes Demián Bichir as Alex, the cartel’s corporate style manager. Bichir — who was Oscar nominated for playing an undocumented immigrant in 2011’s wonderful A Better Life and also portrayed the corrupt Tijuana narco-mayor Esteban Reyes in the Showtime series Weeds — hands in another solidly etched performance that’s literally eye popping. In Steven Soderbergh’s 2008 two-part Che, Bichir portrayed Fidel Castro opposite Del Torio’s Che Guevara. As Lado, the cartel’s sneaky plotting enforcer, Del Torio not only steals everything in sight, but every scene he’s in, too. Another standout is Travolta as the opportunistic Federal agent.

Savages perpetuates many of Stone’s recurring obsessions: There’s a great montage of a lotus opening and an image of Buddha, suggesting Stone’s presumed Buddhist bent, plus his empathy for the Third World. The Mexican milieu is reminiscent of Stone’s two Castro biographies and of his great 2010 documentary about Latin America’s leftist presidents, South of the Border. Travolta’s DEA law enforcement official represents the director’s jaundiced view of the U.S. government, found in his 1980s antiwar masterpieces Platoon and Born on the Fourth of July (unless I’m mistaken, look for that autobiography’s author, Vietnam vet Ron Kovic, in a cameo in his wheelchair), as well as Salvador, plus Stone’s epic condemnations of the powers that be in his trio of presidential pictures: 1991’s JFK, 1995’s Nixon and 2008’s W. Savages’ economic subtext recalls this stockbroker’s son’s concerns with the predations of capitalism in 1987’s Wall Street and its 2010 sequel.

Savages, however, is more topical than political (although it has some incisive observations about the PRI winning Mexico’s presidential election), and it joins the swelling ranks of films inspired by Mexico’s terrifying Drug Wars: The feature Miss Bala and the documentary Reportero, both recent Mexican-made films. And it is, on the surface, far closer to Stone’s 1990s crime movies, Natural Born Killers and U Turn, than to his overtly political pictures. In once crucial way, however, it revisits Stone’s inner fixations, with its bloody depictions of the violence Stone presumably witnessed in ’Nam, and the revulsion such cruelty and slaughter conjures up within his soul. I suspect the Charlie Sheen character in Platoon is extremely autobiographical (in spirit if not exactly in letter), and who knows what Stone saw firsthand during his Indochina stint and how it damaged and affected him, turning him into an avenging artistic angel of peace. In any case, one suspects Stone knows all about reverting to savagery in order to survive from his Vietnam misadventures.

As with 1991’s The Doors, Savages has a scintillating soundtrack, ranging from Brahms to Bob Dylan to Peter Tosh to new music composed by Adam Peters. At the height of his creative powers, with his finely tuned cinematic sensibility, Oliver Stone remains the movie Michelangelo.

To read Ed Rampell’s interview with Oliver Stone about Savages see: http://www.festivaloffilms.com/blog/2012/07/05/exclusive-interview-with-oliver-stone-the-savage-is-loose/

Leave a Reply